Reinvent the business model – the most important lever to tackle the environmental shift

In recent years, companies and industries are starting to rethink their products and services in order to achieve ambitious environmental goals. While these eco-design efforts are necessary, they are still object-bound while ignoring the whole system.

Meanwhile, the environmental impacts of industries and companies equally lie in their production and business models, which were often designed in the 19th century, when environmental criteria were not taken into account.

No matter how hard we try to "fix" or improve this faulty system, we will never achieve the target level of environmental performance. As environmental targets become more demanding, it is necessary to move away from the optimisation thinking and design new systems that are compatible with current environmental issues.

Reinventing to break free from past design choices

Our current industrial and economic models are a legacy of the industrial revolution of the 19th century, and of design choices that did not take into account the scarcity of raw materials, or upstream and downstream pollution during the manufacturing process. These are models that have mainly responded to the challenges of economic performance, speed and efficiency.

Companies therefore find themselves optimising the environmental performance of systems that were not originally designed to do so - systems that are energy-intensive, raw-material consuming and waste-inducing. So long as companies remain in this optimisation mindset, they will come up against the very limits of their model and, in most cases, will not be able to meet the environmental objectives defined by current or future regulations. This is a phenomenon we call the "invisible R&D wall", which is well known in R&D activities. When optimising a system, initial efforts are well rewarded and significant improvements are quickly made. But, over time, it becomes more and more expensive to optimise the system and the performance gains are smaller and smaller.

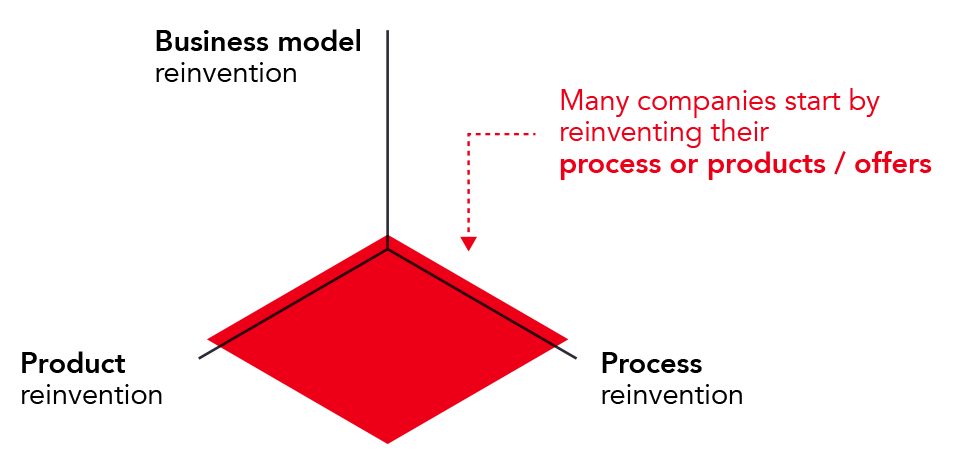

Companies, faced with the climate emergency, must therefore opt for Reinvention, a process aiming to thoroughly reinvent a product, a service, a business model or a historical process, by freeing themselves from the choices and design models of the past. A good example of reinvention is the transformation of Umicore from a mining company in Belgium to a precious metal refining and recycling company in the 2000s. This transformation required the total reinvention of its activities and expertise. The example of Umicore given earlier corresponds to a radical transformation of the company's positioning. A company can in fact play on one or more dimensions of reinvention to drastically reduce its environmental footprint.

Let's take the example of a leading European packaging company, with whom we started working in 2019. Our work with the R&D team initially focused on reinventing the manufacturing process, which resulted in the reuse of over 30% of thermal energy, saving €1.5 million per year. In 2020, we tackled the second dimension - their products, by completely transforming the packaging architecture. This reduced the amount of raw material used, and therefore the associated CO2 emissions within the manufacturing process, by 40%. The order of reinvention naturally corresponded to the expertise of the R&D team of this manufacturing company. Work on these first two dimensions has already yielded significant results, but it is possible to push the ambition even further.

The company's business model is based on a single unit and single use sales model. The company is therefore still attached to a system that is very energy and resource intensive. Reinventing the business model therefore represents a significant potential for reducing environmental impact. Tackling this dimension means a profound rethinking of product use and functionality, the value chain and relationships with suppliers and customers.

Given its systemic nature, this dimension often goes beyond the traditional scope of business, and therefore, is understandably the most difficult to address. But precisely because of its systemic nature, it can enable us to transform entire industries in a profound way, with significant potential for reducing environmental impacts.

There are examples of companies that are beginning to experiment with this third dimension of reinvention, rethinking the rules of the most common business models inherited from previous centuries: single use, single buy and individual use.

Tackling the third dimension of reinvention: leading examples

Single-use or disposable products are products with a limited life span. One of the most striking examples is that of the giant tire manufacturer Michelin, who has experimented with shifting from the model of selling single-use tires to a pay-per-use model. This model aligns economic and environmental interests, encouraging maximum use and life of a tyre. It is also more beneficial for customers, as it provides significant cost savings. For road transport customers, for example, good equipment maintenance can reduce fuel consumption by 2.5 litres per 100km for long-distance transport (or 8 tonnes of CO2 emissions).

On the other hand, the single buy model corresponds to products that can potentially last indefinitely, but customers tend to want or own more than one, such as clothes, shoes, kitchenware, etc. Several established companies in the textile and fashion industry are beginning to find answers. For example, Kering recently invested in Vestiaire Collective - a second-hand marketplace for luxury clothing now valued at $1.7 billion. To take the model a step further, one could ask whether it is possible to limit the loss in value of these products over their life cycle, or even increase their value. This is the principle of upcycling or Kintsugi, which involves, for example, repairing broken pottery with gold dust.

Last but not least, the individual use model can be easily challenged for products that have a long life but are not used very often. It is common for every household to own them, even if their use is not always very frequent, such as specialised utensils, tools or even parts of the home. Airbnb has become a classic example of monetising the unproductive and little-used spaces of a household. The platform creates new suppliers and customers of rental spaces by monetising small rental units, such as the provision of a room for a short period of time. The same model of sharing and mutualisation applies to household appliances, with tool rental platforms such as Bricolib, Allovoisins or Kiwiiz.

Conclusion

Major challenges such as the climate emergency and environmental degradation require profound and systemic transformations. And this reinvention must be tackled on three dimensions - process, product and business model. Only by deconstructing the historical models on each of these dimensions, and by questioning the most deeply rooted elements, that we will start building build these new, more adapted models.

To succeed in this Reinvention process, companies must reexamine: What dimension of Reinvention was previously addressed? What results have been achieved? Would it be interesting to go further and tackle other dimensions or perimeters? For some industries such as ready-to-wear, automotive or consumer goods, if we don't address the business model dimension, we are not addressing the most important lever and risk missing out on the opportunities for truly meaningful change.