What if you have come up with the Hyperloop?

When Elon Musk published a 58-page white paper on the idea of Hyperloop in August 2013, everyone got excited (once again) about a tube-type futuristic train that could get up to 400km/h - you can travel from Limoges to Paris in 45 minutes for example.

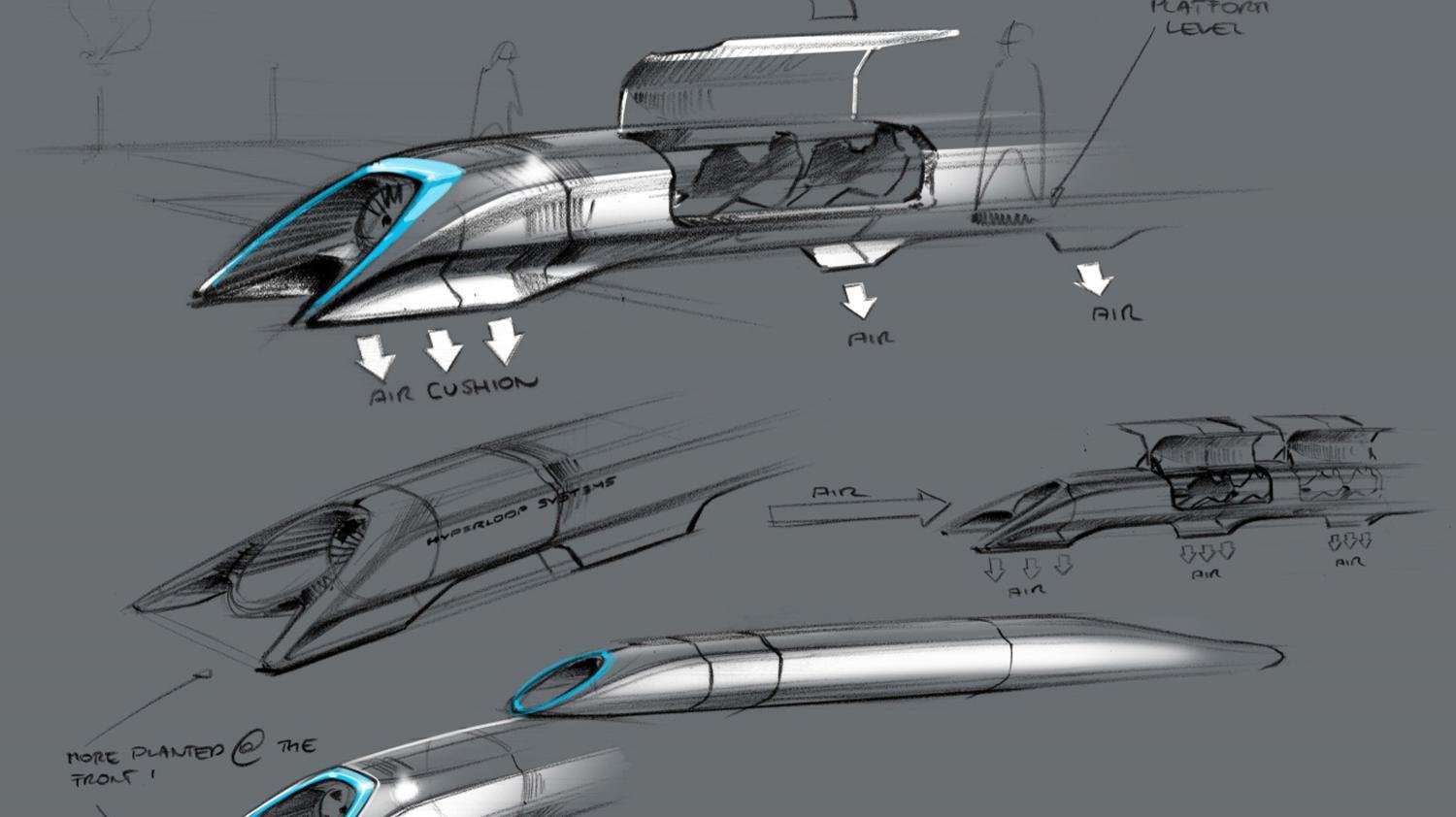

High-speed trains are too expensive and too slow in Musk’ opinion, and given that the previous ideas such as vacuum-sealed tubes running on magnetics, or pneumatic tubes won’t work, he proposed us a low-pressure system where “Sealed capsules carrying 28 passengers each that travel along the interior of the tube departs on average every 2 minutes from Los Angeles or San Francisco (up to every 30 seconds during peak usage hours).”

The initial proposal included two versions of the loop (pod plus cargo and passenger version) - both cost around $6 to $7.5 billion, while the California high-speed rail project will cost around $70 to $100 billion.

Concept draft of Hyperloop

The Hyperloop concept has been explicitly "open-sourced", and other companies have been encouraged to take the ideas and further develop them. We don’t know yet if this new type of transport might actually work better in California or on Mars, but it is very interesting to track back the thinking process of Musk - from the argument that high-speed trains are obsolete and irrelevant in tomorrow’s technological, economic and social context, and that we need different transportation.

Figuring out this process allows us to understand the core principles of how any breakthrough innovation is born and later brought to the market.

Intensive generation of ideas

We will use the C-K method as an analysis standpoint to understand this seemingly futuristic tube transportation. Guarantee you that this is not just another boring subway system we already enjoy in Paris, London, or New York.

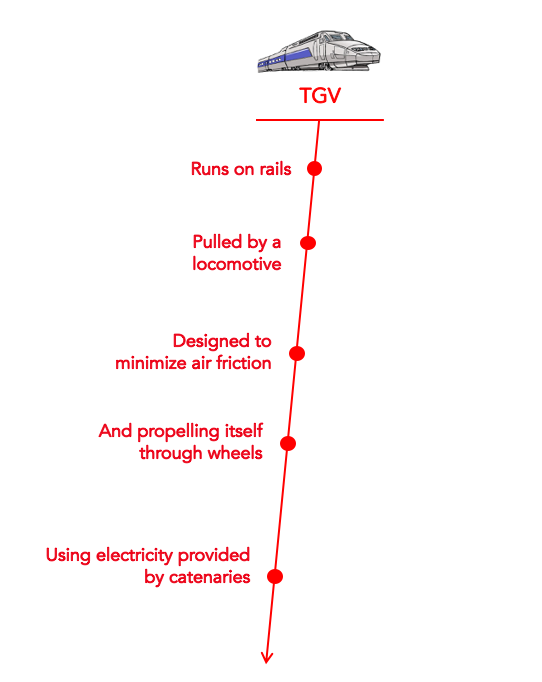

The first step in the thinking process is to build the identity of a high-speed train, one we have imagined since the 1970s. In this step, an innovator will spend time describing and thinking about the current object, the service, or the process in a very complete and systematic way.

This description includes fundamental elements of the object, such as the list of components, its mode of operation, etc., that without these characteristics, the object is not itself anymore.

Our mind does this almost on a daily basis without us realising it. Imagine yourself going to buy a new personal computer, and you are looking at this great notebook. Your thoughts would be: “Oh, look at this thing. It’s light so that I can carry it around without hurting my back. The screen is full HD, which allows me to watch movies comfortably. It has 3 ports USB and 1 port RJ45, so it’s convenient to connect to many devices. The price, however, is quite over the top...”.

The human mind scans and takes notes of a daily object’s identity, such as a mango, in only seconds, yet for more complex objects and systems, it might take a few hours. A systematic mapping of an object’s identity, in this case, can contain up to 100- 300 items. In the case of TGV - Train à Grande Vitesse (High-speed train in France), the list of identities will look like this in the very beginning:

This description is the innovator’s starting material

“If I had 20 days to solve a problem, I would spend 19 days to define it.”

Once the object’s identities are built, we will question each element to imagine and invent other possibilities, based on the question that the human mind loves to ask: “What if?”. We ask this question almost on a daily basis, and this is surely what an innovator has to ask himself and his team.

This series of What if? will build a tree of possibilities - a large cartography, to which our initial description is enlarged to all directions: "what could be done other than having wheels that propel the train?”, “what if there is no wheel anymore?”.

But just breaking down the object’s current identity will not be enough. If we force our brain to think that a train is no longer powered by wheels, the next step is to imagine other alternatives of propulsion, and these alternatives can either remain internal or external.

By going on like this, we will build variations on each characteristic. Take one trait of TGV today as an example - propelling through wheels, it is through practice that we force ourselves to ask questions as follows:

What if wheels are only used to guide? In this case, what if propulsion is still inside? Or what if the train is towed?

What if there is no wheel at all?

By changing the paradigm, for friction: instead of trying to diminish them, one could imagine that they do not exist! (“in a frictionless environment”). Or regarding the characteristic that trains nowadays are “pulled by a locomotive”, we can ask: What if each wagon of the train can propel itself? Which means either it can travel alone by itself. Or can it travel with others in a modular fashion?

All these variations, either individually or combined, allow us to imagine many different and extremely interesting solutions of tomorrow's train:

You can see the known example of the monorail without wheels but with an air cushion, yet at the same time arrive at a much more far-fetched solution such as a modular-wagon train where each wagon has its own route and only regroups when necessary, or a capsule-cable-car train

In fact, most of the ideas didn’t even make it here. It's usually at this first step that companies kill radical innovations without even giving the second look, by engineers and marketing people and the board saying things such as:

“That’s not what we do!”

“Let us deal with it as we usually do in R&D!”

“We should immediately invest a lot in this ( this = an incremental innovation that we usually do in R&D)!”

By challenging the status quo of an object, we force our brain through an intensive idea generation to generate interesting concepts in a very systematic way to go much further than we initially could. Yet something is still missing.

These ideas are not all new and robust. Some were been built (monorail for example) and others are technically possible yet do not imply interesting economic and social impact. Which values would a cable car public transportation add up to urban planning and urban life experience? Not much...We need to search even further.

Knowledge to explore

Coming back to the starting point of “I want to build something cool to replace the TGV”, generating many cool concepts, as you know, is not the hardest part. The other classical innovation methodologies remain in this circle of variations of the known and the existing. We cannot solve new problems with the same understanding and know-how we already have in our industry. And that is how C-K comes into play with its power: instead of staying on that tree of concepts, we will explore knowledge beyond our own field of expertise.

This is how the idea of the Hyperloop came into that landscape of ideas. Working in the aerospace industry for years, Elon Musk knows that removing the air and the friction with the ground drastically decreases the energy needed to power a moving object.

Thanks to this contribution of external knowledge, he would complete the tree with several options: a vacuum tube to remove the air, with levitation or air cushion to remove friction. Since the friction was removed other options have to be explored to power the train.

By accumulating new knowledge on propulsion technologies, common in the aerospace industry, we would have learned, for example, that navies developed electromagnetic propulsion missiles with an extremely strong initial pulse or we would know as well basic knowledge about jet propulsion. The accumulated knowledge would also allow us to see how the modularity solutions could couple with the previous ones.

The Hyperloop depicted by Elon Musk is not more interesting and feasible than these above-mentioned train concepts at first look. But to actually come up with a concept and back it up with a solid knowledge base is another story.

| "It is important to view knowledge as sort of a semantic tree — make sure you understand the fundamental principles, ie the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang on to”

- Elon Musk

Knowledge to decide

Once the tree of concept and the knowledge base has been grown, different options are available (monorail, modular wagons, individual capsules, vacuum tube, electromagnetic propulsion, jet propulsion, air cushion...). The next question for innovators now is to decide which ones are commercially, technically and socially interesting to be turned into a reality.

The simplified version of the C-K tree, presenting different alternatives to high-speed-trains-as-we-know-it

In which options should we invest our effort and resource available at the moment? There are two possible choices:

Choice #1: “Well, we will do this because I like this idea and we can do it”

In this scenario, we catch the first idea of the Concept space that is measurable with our classical performance criteria and follow without knowing why we would not go in other directions. (Wrong choice!)

Choice #2: “We have systematically scanned all available options and explore these options by learning and creating new knowledge in the Knowledge space at two levels.

Level 1: a macro analysis to decide between options and how some are better than others - here, read this 50-page paper.

Level 2: several prototypes to validate chosen options. At the end of the day, we choose this particular option because it is technically, socially, and commercially interesting” - said Elon Musk. In this case, we adopt a method that allows us to orient ourselves, make a constructed decision, and move in a clear direction, knowing why it was chosen.

That's what the C-K method is: a piloting tool to explore the unknown. In the design and exploration phase, it helps us to expand efficiently the spectrum of possibilities beyond the expertise firms already own.

While in the pilotage phase, it provides a clear vision of all innovation strategy choices- with a set of related critical knowledge to explore and acquire in firms' stocks of know-how. With this powerful device, it is now your turn to come up with the next big concept.

This article was written by Anh Nguyen, content producer at Stim and Waste is a Failure of Design.

Download our book « Stim decrypts: Innovation methods » (in French), where we use the C-K method as an analytical framework to decipher the most popular innovation methods: Bono Hats, Design Thinking, Lean Startup, ASIT, and the Ocean Blue Strategy.